In San Francisco Back for duty on board ship after the leave had ended, there was still plenty of time for liberties in the San Francisco area. It seems we were in for about a month at Hunter's Point Navy Yard.

Two meetings with women (along with other guys on one, and alone on another), resulted in much less activity on my part. Maybe I'd learned something from my prior misbehavior, or maybe I didn't appeal to them that much. Whatever it was, I was glad it ended that way. I was not, however, finished with the drinking bit.

Reminded of Earlier Incident in Boston One time I recall heading into a long, narrow bar which was scarcely lighted so that it was difficult to find the washroom. I noticed men staring and gawking and turning their heads as I walked to the back. It finally hit me! These are "queers" looking for a date or a "make." Remarks were made as I walked in and out, making me sick to the stomach. I hated what their M.O. was in life more than I can say—not that I'm that different today. The reason? It's because I'm going to relate something that happened in one of my liberties (alone) in the Boston Commons, that historic setting.

I was broke as usual and just taking in the sights of the gardens when an Army or Air Force officer approached me (Army, I think) asking if I cared to join him. I had in mind he meant he was "buying." We walked around having all the non-commissioned guys saluting this guy while I walked with him. It felt good to gain such respect. He eventually said he had some liquor at his hotel and invited me to accompany him there. All the while I kept asking if he knew of any girls we might take along for a dinner or to his place. He avoided the question to where I was slightly annoyed, even a little suspicious—but still naive.

When we got to his hotel, all the employees addressed him as though he were someone special. We took the elevator up several floors to his room. Once there, he suggested I take a "nice cooling shower." But I refused (several times) and asked when he was going to bring the drinks out.

Whether he made a move or a suggestion which awakened me, the result was the same. I stormed out of the room saying something like "You're nuts!"

Taking the elevator back down to the street level, I shouted to the operator, "You've got a 'queer' in there!" I don't think he was overly shocked to hear my revelation. They all probably already knew it.

All that to say, when I was in that bar it became my second encounter with homosexuals. I'd never, before the Boston experience, known about such people and their lifestyles. It was totally contrary to my thinking, and it almost made me nauseous.

Sick way to leave the Ship Before closing out San Francisco liberties, I want to show how some people's thinking can become even more perverse than what mine was (and some were surely that).

One of our crew members, a guy who was nice looking, but who portrayed a certain amount of femininity in his mannerisms, came back to the ship one day just before we were to ship out. He went to sick bay, turning himself in as one who had contracted syphilis or some other venereal disease. The unbelievable part of the story is that he told us he deliberately stayed with a woman known to have been a carrier of the disease so he could avoid going back to sea and war duty. Sick, sick, sick!

Guess I was wrong (maybe not, though) about his femininity. But anyone who'd do what he had—in my opinion—needed more than physiological treatment!

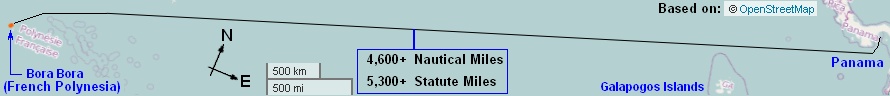

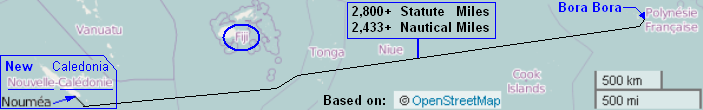

Back to the South Pacific On June 1, 1944, the ship again got underway for duty. Leaves were completed, repairs made the ship seaworthy, and we were ready to resume duty where we'd left off a month back. But our assignment had been changed.

Hunter's Point Navy Yard behind us, and the Pacific before us, we proceeded to the Central Pacific, having been assigned to escort duty between Pearl Harbor and Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. This was during the time of the invasion of Saipan.

The S-28 A month or so later (July, '44) we conducted the search for a sub, the U.S.S. S-28.[11] It had failed to resurface after a practice dive. A regular Navy Commander of Submarine Division 41 was assigned to our ship to oversee the search. We did eventually find five oil slicks, but no survivors or debris were found. It was another of the sad events in my navy life!

Thinking of the sailors who were trapped in that sub, and knowing what they must have felt and thought, was almost maddening. We just looked about helplessly while they no doubt hoped and prayed something could be done to bring them back to the surface. It is incidents such as this which are fixed in my memory, uncomfortable as such thoughts can be.

Pilots and Crews Rescued The next order to duty was to act as a training ship for submarines operating out of Pearl Harbor. While assigned to this task, we were called upon for rescue work. An SB2c Helldiver had crashed into the sea, and we were to try recovering the crew. We were guided to the location by search planes, but by the time we arrived, it was already dusk.

This rescue attempt became more complicated by a damaged PBY which had landed to take the SB2c fliers aboard, and was then damaged by heavy seas in an attempted takeoff.

The ship's record reads: "After several attempts were made in the rough sea to rescue the planes' crews, the PBY sank, spilling the men into the sea." But as I (and this is unofficial) remember the incident, we actually bumped into the PBY and "helped" it to sink. It couldn't have flown away, anyway; it's just the saving-face way this was written that caused me to list my opinion.

During the rescue attempt of those men, ten in all, another frightening discovery was made: As the ship pulled closer to the PBY, schools of sharks were seen swimming under the floundering men, presenting an even greater danger than had previously existed. To offset this danger, small arms fire was used to drive the sharks off as rescue attempts continued.

This worked pretty well for a time, until gasoline fumes from the sunken plane made it too dangerous to continue.

We had a gunner's mate second class on board who was quite husky. His name was Ed Bernik[12]. He dove (or "dived" if you prefer) into the smashing seas and began swimming toward the exhausted swimmers to give aid.

While this was taking place, two of the ship's officers, Lt.(j.g.) John F. Cykler and Lt. Nat Brown had attempted to float a raft to the downed crews. In the process of that attempt, the officers were also cast adrift.

Eventually all the downed crew members and the ship's officers were safely returned to the ship. Ed Bernik's bravery in that rough sea and in the presence of those sharks surely called for some sort of commendation.

Fall, 1944: A Very Sad Time in my LifeLast Letter from Ruth Ruth Ashcroft, my one and only true love whom I'd so carelessly abandoned in my fear of certain marriage, began to again warm up to writing to me. In time the letters returned to the kind we'd been exchanging in the past.

It should be said that I initiated the return to writing by letting her know how bad I felt about not agreeing to meet her in Chicago. I also didn't want to give up that loving relationship we'd built in all those months, and I thought that given proper time, we really would probably marry one day. Her sweetness in accepting my apology made me feel all the more that she was meant for me!

As happens in real life situations on a regular basis, the late fall of 1944 turned out to be a very sad time in my life. Our ship hadn't received incoming mail for some time (we moved about so much), and on this particular day I received several pieces of mail—a most precious commodity to a serviceman overseas. I eagerly glanced at the return addresses to see which I'd want to open first, and in spotting Ruth's as one of them, I knew it'd have to come first.

It began, "Dear John." You've heard of such letters being used in jest, but this was of the genuine variety. The introduction left no doubt in my mind I wasn't going to like what I'd learn in that letter.

Ruth had met a U.S. Coastguardsman. She didn't say when or how. She had been writing to me as though everything was patched up, but now she had found another. I couldn't believe what I was reading. "How could this be?" I reasoned. "Would she have done this same thing had I met her in Chicago and went back to sea saying we should put off marriage until a later time?"

In later years I thought of how I wished I'd saved that letter. It would have come in handy right now to list exactly what else Ruth had to say in it. In any case, this romance was over for good!

Only God knows what was in Ruth's heart and whether my absence would eventually have led to the same conclusion had I not miscued at Chicago. Maybe I didn't know her as well as I thought I had. After all, a one night romance followed by correspondence didn't give me much to go on. I did save her picture for years until one day my wife said she'd seen enough of it. I guess I kept it to show others that a beautiful woman such as that had once considered marrying me. Beauty really is what the old cliché calls it, "skin deep."

All that to cover just the first letter I'd received. There were two of the remaining three which gave bad news, too.

News About Phil The next letter which I opened was from Mom and Dad. It could have been that my sister Marie did some of the writing for them, though I remember seeing Mom's handwriting mostly. I wondered what news might be coming from home and thought it'd be good to get some cheering-up. I was wrong in thinking there'd be anything in that letter which would accomplish that goal.

As I recall, the greeting was immediately followed by the main purpose of the letter, to tell me my brother Phil was listed as "missing in action" somewhere in the mountains of Italy. This had happened some sixty to ninety days before Mom and Dad received a telegram from the War Department. That meant he could be alive, or he could be dead. Naturally, most, having the human nature we do, take on the worst possible scenario; I certainly did!

Telegram to author's parents about his brother Phil (See here for more about Phil.) [So] for that day, I'd lost Ruth [and] also my older brother to the war. I'm sure it must have caused mental stress and embitterment, coming as it did in a double dose of bad news!

Murder Never Solved If you can think back to the place I'd mentioned meeting Emily Wnuk, the sister of the girl with whom I worked at the Western Electric Company, and the one who visited me at Great Lakes Naval Training Center while my folks were there (boy, this is a long sentence!), this third letter I opened came from Emily's sister.

The first thing which fell out of the letter was one of those announcement cards (or whatever they are properly titled) which give data about someone's death. I quickly turned it over to bypass the descriptive data so I could see whose picture would be on the other side. I almost dropped to the deck when seeing it was Emily's picture. The birth/death dates were listed along with her name under the picture.

Before reading the letter and the inserted newspaper clippings, I had to take a deep breath. "How could all this happen to one guy in one day? Lord, give me strength; I can't hack it!" I prayed.

Regaining my composure, I continued by reading the letter and the newspaper clippings to see what had happened.

The newspaper articles told of a tryst in which Emily evidently was to meet an acquaintance, boyfriend, date—or whomever—at a specified place in [Gage] Park[13]. I've since lost or misplaced those newspaper clippings, so I can't be certain, but I think this may have occurred toward late afternoon when work hours were over.

She didn't come home that night, so Emily's sister called the police department to report her missing. By that time (early the next a.m.) the police had already found Emily's bludgeoned, bloody body shoved under some shrubbery in the park. Much of her hair had been pulled from her scalp as though in a ferocious battle for her life. All identification had been removed, so the sister had to identify the body.

An article dated at a later date listed this murder as another of Chicago's "unsolved crimes."

From the time I'd last seen Emily at the Naval Training Center, I really never intended for ours to be anything more than a friendship. But having read of her demise in that cruel manner, my heart went out to her sister—and, in a way, to Emily in her last moments of life. Man's inhumanity to man; a mystery I'll never understand. Nor do I understand how such crimes can remain "unsolved."

Later: Hopeful News Sometime later I got another letter from my folks telling me they'd received another notice from the War Department advising them Phil had been listed as a prisoner of war.

The updated information about my brother Phil's capture came later when Mom and Dad got a letter from him via the Red Cross (I think that's how their mail got through—the Geneva Convention Rules, I guess).

He said he and his men (he was a sergeant of some sort) were atop a hill or mountain where a crevasse dented the top, allowing protection or cover.

While manning the side which was thought to be a likely assault route by the enemy, they were surprised by a number of enemy soldiers (German, I believe) from the opposite side. With guns pointed at your back, you aren't likely to do anything foolish; so they were taken prisoner.

In reading earlier accounts of Phil's disposition as compared with mine, in later years he maintained that same composure. He never was a braggart as I tended to be if some accomplishment had been reached. So it didn't surprise me when years later I was told by sister Marie he kept the diary he'd written all those months in the prison camp to himself. To this day I don't know what really transpired in his capture or what prison camp life was like.

Someone had told me Phil had reached the rank of a Staff Sergeant (maybe even one step higher, not sure). "Ranks," he was supposed to have written, "are quickly achieved in combat when squadron or platoon leaders are killed. Someone has to take their place, and that's how I went from a private to where I am now."

One thing I recall hearing of his prison life dealt with food and cigarettes and Red Cross packages they'd receive occasionally. Since he didn't smoke, he'd exchange the cigarettes for something edible. Whether he said this or not isn't certain. But I had heard from someone, somewhere, that prisoners hard pressed for food in certain camps, those near to starvation, caught mice and rats and ate them to stay alive. I can see where that just might have happened.

One last thing before closing out Phil's capture, he did receive a Purple Heart[14] for what I'd always thought was some kind of wound he'd gotten in battle. But he is supposed to have stated it was merely for "frozen feet" he'd received the award.

Since I don't know the date of Phil's subsequent repatriation, there's no point in trying to list it in a time sequence later on. It seems it was in the spring of 1945 when Germany's military was on its way out, and the allied forces were taking great strides toward ending the war there. He eventually was discharged in something like August of 1945.

Southern Self The turmoil of bad news letters over and my hours filled with duty time to occupy my thinking, I got back to the everyday shipboard life. And some of the stories of that life follow.

There was one tall, lanky Southerner on board our ship who had a distinct drawl, one which was similar to that which Williams had, though even more pronounced. He presented a comical appearance by his large, "flappy" ears to go along with a smile that was almost as wide. He was a happy-go-lucky individual who never gave anyone the idea he was unhappy about anything. I liked him.

In port one day and a swimming party authorized, Self (the first name I can't remember[15]) got up on the yardarm of the ship to jump into the water. That yardarm had to be at least sixty feet or more from the level of the water. It must have been that most of the ship's officers had gone ashore, as I doubt this would have been permitted under normal circumstances.

Self jumped off, clowning all the way down by wildly moving arms and legs and shouting silly remarks, hitting the water with an enormous splash. That was a very dangerous and daring fete, if not "unwise."

Another thing about Self was his singing. When mail would come aboard and he'd receive none, he'd sing "No latter today, love; I have waited so long...!" The "latter" was his verbalization of "letter." Since many found themselves in the same boat—no letters received—they tended to feel comforted by the humorous manner in which Self entertained them.

A year or so back I'd gotten a letter from a former shipmate who said he'd gone on a tour of the Southeast U.S., looking up former shipmates as he traveled. In looking for Self, he learned he had passed away. No details were given as to what had happened to him. I know he was a little younger than I was when we were shipmates.

Though I hadn't seen or heard from Self in years and years, this disclosure about his passing saddened me greatly. There were also a couple of others who had been found to have passed away in that shipmate's trip, but I didn't know them as well. After all, we were all getting up in years in 1990 when that trip was made, and I know others, too, have met their Maker even before that time.

Richard Curran One day I was looking through my navy memorabilia, and I came across a letter from my friend Richard ("Red" to me) Curran. He's the freckled, red-headed kid who bunked under my bunk and the one who I'd felt I had to sort of protect from others. Don't get me wrong. He was a fiery kid who could fight for himself!

In the letter he reminisced about our shipboard days a little, but he also spoke of my brother Phil and I seeing him at one of the rail stations in Chicago on his way through to Wakefield, Massachusetts. I just slightly remember that visit, and in relation to a time sequence, this is premature, too; for it happened in 1947 when I was in an airline training school. But I want to cover that story so I don't forget to list it. (Letter written in 1947—not the train station meeting.)

Red had told me he'd allow me to call him "Red," but it was obvious he preferred "Richard," his real name. He told of his brothers who had city or municipal jobs in or around Wakefield and that many in the community thought they had a drag of some sort to get them. He assured me none had done that and that they'd all earned the jobs they got. He was either already on the local police force or getting ready to go on it.

Then Red went on to explain I'd met the one brother who became a county cop (I think). That meeting would have had to take place in Wakefield, so I must have made at least one trip home with him to meet his family. That trip is only vaguely in my memory. It had to have happened while we were in Boston.

What happened in the years that followed, I don't know, as I have no further correspondence to show that we communicated with each other after that. Maybe my moving about the country and into so many different jobs kept me too busy to keep up with writing. I'm sorry it turned out that way!

Back to ship's activities. From October of '44 to March of '45, we escorted convoys of mostly fast tankers in between Eniwetok and Ulithi in the Western Carolines and Kossol Road in the Palau Group. The fuel being delivered was to be used by the Third and Seventh Fleets operating out of the Philippines and to the north in the vicinity of Formosa and Nansei Shotō.

Becoming a Radar Operator Somewhere along the way while on board ship, I wanted to explore the possibility of getting into a line of duty with more sophistication than what a seaman's job had to offer. I don't know exactly when I began the search, but I eventually found myself hanging around the signal bridge having learned the Morse code, semaphore and how to use the blinkers. But no openings existed in the signal bridge crew.

Having been a seaman first class for some time, the only way to advance in that crew or group was to advance to Coxswain and then Boatswain's Mate. That didn't appeal to me, and thus the search for another gang (as they were called departmentally).

One of the signalmen advised me he'd heard of an opening in the radar shack crew, so I checked it out and was eventually accepted for that duty.

For the remainder of my stay on the Crouter I still spent much time on the signal bridge, being given the privilege when in port to signal to other ships on which I had relatives or friends assigned. It worked better than the mails by far, not that I always got a response to my messages, however. Some of the vessels were so large it was difficult to locate the person sought, or the guys who received the message just didn't want to bother. It was fun just the same!

One of my cousins who is near to my age, served on the Saratoga[16], an aircraft carrier. I slightly recall having gotten a message through to him one time while in some port. We didn't get to meet, however. His name is Richard Novotney.

Being in the radar gang had its pluses. No more ordinary seaman cleanup type work or bridge watches were part of my work. I spent all my duty hours watching a "scope" looking out for any kind of unusual "bleeps" on the screen which might indicate there was a surfaced sub, a floating object, or even aircraft in the vicinity. Any such irregularities were immediately reported to the bridge where it was decided if a trip to the radar shack was necessary for an officer's observation as to whether further action needed to be taken.

One big problem I had with this gang was partly my own fault. I never was able to kowtow to anyone who seemed to demand attention or subservience. Mine was never a servile or submissive nature. And that's what I felt the two who headed up

the gang looked for. We got along as far as getting the job done was concerned, but I never made any "points" in their book. In the navy (and most likely other branches of the military) it was called "brown-nosing." I'd never justifiably be accused of that!

I had my third class rating for over a year when a new man came on board, a seaman first class. He got into our gang because our Radar Technician left the ship, giving one of the second class guys a chance to take his job. That then left an opening in our gang.

This guy (and I won't use names because he might still be living and able to read this somehow) had all the qualities I didn't. He fit into this remaining second class guy's qualifications for "brown nose first class." And the three of those guys eventually made a lovely trio! (I may have exposed names by this.)

The crux of the story is that this new man had been a rank under me, but by the time the ship went back to the States for decommissioning, he'd achieved a second class rating, one above my rank.

Is it possible I'm viewing what happened in a very subjective mode and that this really didn't happen the way I'm describing it? It's possible. But, naturally, I'm inclined toward thinking it took place as I've listed it. The guy who surpassed my rank was a nice guy, but I didn't like the way he got his rank.

Left All Alone When still a seaman first class, I remember an incident which perhaps told more about my nature than I'd like to admit.

A bunch of us seamen had a beef about some kind of treatment from the Coxswain. He was a wiry, smart-aleck who had a dirty mouth, a regular navy man who thought little of those who were just "reserves." So we decided we'd go to the executive officer and air our problem. This was to be done in a collective effort by all who'd agreed to the plan.

By the time we knocked on the Exec's hatch (door), I turned around to find myself standing there alone. All the others had "chickened out."

The officer heard my story or complaint, though with grumpiness, and he concluded I had a "belligerent attitude." It was the same as trying to present your case in a court of law to a judge. He often won't let you say what you have to say, and if he does, he'll still rule against you. This meeting, I think, resulted in an insertion into my records to show I was a belligerent person. Not much gained, huh? Not much backing, either!

Hanging on the Yardarm Though we in the radar shack didn't have to participate in "swab jockey" type work (that of seamen), we did have to maintain our own gear. One of those pieces of gear, the antenna or radar dome, was located on one of the yardarms. I remember very clearly when my turn came to get up there and hold a bucket of paint and a brush in one hand while tightly clinging to the ladder on the way up, all the while trying to do what was nearly impossible. The "ladder" was merely metal rungs going up alongside the mast. You ought to try that trick sometime if you are looking for something different to do.

As little as one rung at a time meant you had to pull yourself up while holding the bucket and brush, and that wasn't a simple matter.

But worse than the climbing was trying to hold on to the guy wires (probably not the right word for them) while holding the bucket and dabbing paint onto the dome. All this while the ship is pitching to and fro and rolling from side to side. Here was a place where a third arm and hand would have come in very handy!

Had the yardarm been five or ten feet above the deck, maybe it wouldn't have contributed to the fear, but it had to be at least forty feet or more above the main deck and several more feet to the water line.

I was being the usual hypocrite by acting as though it didn't trouble me, but I kept it all inside to save face and show who and what I was. The cramps in my arms, hands and legs told me what a liar I was.

When I survey the possibilities of what I could have been a part of had I not gone into the radar gang, I realize I really had it pretty soft there. We enjoyed hot drinks made from a prepackaged chocolate mix regularly, something the deck crew couldn't dream of enjoying. I don't know who managed to get it on a regular basis or how he went about it, but it sure hit the spot. After all, how many other work areas had their own hot plate? Very few! Yes, I had it pretty good there; and maybe some of the guys I berated in my story were the very ones responsible for acquiring the hot chocolate! I'm too judgmental, too often.

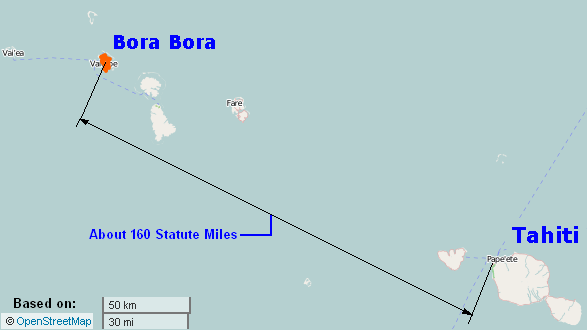

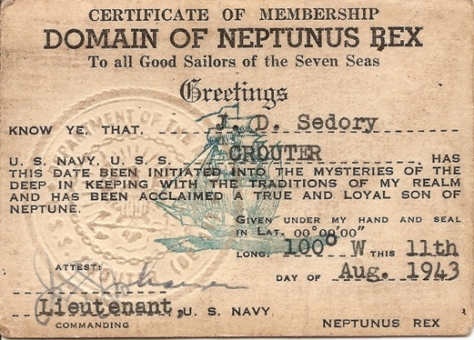

Ancient Order of Shellbacks[Editor's Note: This event took place on August 11th, 1943 (before arriving at Bora Bora).]

One of the most trying times in my navy life took place during an initiation tradition for those who had never before crossed the equator, that imaginary line which circles the globe dividing the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

That tradition of an initiation ceremony centers around Roman mythology in which Neptune was said to be the god of the sea. He controlled all the waters on the earth, and thus the ceremony followed that any sailor who'd never crossed the equator before—a seasoned or unseasoned sailor—was subject to it. I believe this also included ship's officers as well, though I believe more discretion was used in initiating these guys, as "Who wants to have an officer on board who will take it out on you later?"

King Neptune was assisted by his queen, Davy Jones, and the Royal Baby in carrying out his orders during the initiation. What transpired in that day (or was it more than one?) was nothing less than demoralizing for the "polliwog" or uninitiated sailor.

The ceremony was a humiliating treatment to the polliwog in order to make him worthy of entering into the Ancient Order of Shellbacks.

The King's Baby in our ceremony was a large (around the middle) first class petty officer or a chief, a regular navy man, one who for some reason never reached top classification in my book. He had that enormous center section covered with oil and grease, and each polliwog had to kiss the Baby on that spot. This, though not the most physically painful ordeal, was for me the most trying to carry out.

Once bending (the Baby was sitting on his throne) to complete the humiliation, he'd grab your head and pull your face right down into the blubber! Oil and grease now covered your face! He'd replenish the supply of oil and grease after each encounter.

Another ordeal was the spraying of salt water from high-powered hoses, which on bare skin stung pretty effectively. This was also done while entering and exiting a long plastic sleeve through which we had to crawl. This in addition to the constant smacks on the rear as we crawled through the sleeve.

Then (as I recall) there was the court session in which the polliwog was questioned, found guilty, and punished. The punishment being a jolt from a rigged electrical (battery operated) fork which was poked at the bare and wet body, the wetness adding to the effectiveness of the jolt.

Some of the other trials led to less memorable events, one in particular being the haircuts—such as running a pair of clippers right down the center of the head. Fortunately, I wasn't treated to that extent. Maybe the guy who had that part of the initiation was someone who I looked up to and who sensed I did.

Having now become members of the Royal Order of Shellbacks and the pains (mostly to the ego) of wounds healed, it then became possible to think of the ceremony as something looked for at some future date where we'd be doing the dishing out rather than receiving it.

Today I have a large certificate measuring something like 14" x 18" which shows I'm a shellback. It gives the latitude where this occurred as 0000 degrees and the longitude as 100 degrees West. It is dated August 11, 1943. Considering the initiation, it is quite a prized memorabilia.

[The author was also issued the following wallet-sized card:]

|